Title: Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber

Authors: Beatrice Da Lio, Daniele Cozzolino, Nicola Biagi, Yunhong Ding, Karsten Rottwitt, Alessandro Zavatta, Davide Bacco, and Leif K. Oxenløwe

Manuscript: Published April 22 2012 in Nature

Note: this part of a series of articles written as final projects for Physics 438b at USC

Introduction

There is and will always be a constant need for ‘better’ ways to communicate information across states, borders, and seas. The recent work done by Beatrice Da Lio and her team regarding the most effective modes of transmission of quantum key distribution (QKD) protocol has given us a look into what the future may hold for communication and the transmission of information. Specifically, their paper, “Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber,” covers how their work looks at the transmission to a core of a multicore fiber is thus far the best candidate for carrying out high-speed QKD protocol.

What even is QKD anyway? Broadly speaking, it is a very secure way to exchange encryption keys from one place to the next via principles of quantum mechanics. This is far different than what we know and use daily, as QKD relies solely on quantum mechanics instead of mathematical calculations. This is done through the use of qubits, otherwise referred to by their longer name; quantum bits, which are the quantum counterpart to the commonly used bit which computers use to store information. To carry this out, a sender, in this work, we refer to the sender as Alice, encodes an encryption key in the form of many different quantum states, typically as polarized photons to a receiver, Bob. It is then left to Bob to take those quantum states, measure them, and then take those measurements and remake the original key that was sent from Alice. However, the work done in this paper takes this general sender and receiver setup and explains the most effective and efficient way to transmit and carry this out.

How they did it

When going forth to manufacture a far more efficient and fast transmission of information, there are issues that need to be addressed. In this paper, the authors explored the use of higher-dimensional qubits, called qudits, to improve the transmission’s functionality by reducing both noise and errors. They considered two options for transmission: coupling each path to a single-mode fiber or each to a multicore fiber. The first option was susceptible to phase drifts caused by temperature and mechanical stress, thus leading to more errors. The second option, using a multicore fiber (MCF), delivered better results with fewer errors but was only workable at very short distances. The authors found that using qudits in the dimension d=4, or ququarts, allowed for efficient transmission with little error at a distance of 2 km. This is a promising start for future transmission efforts, but how did they do it?

In order to avoid the issue of phase drifts, there needed to be a decent amount of work. These phase drifts lead to the disruption of the phase coherence of the superposition of these states, so it is crucial to eliminate the chance of any drifts taking place. This is exactly why the authors decided that the use of MCF’s as the primary mode of transmission; they allowed for a slower rate of phase drifts, but at the cost of requiring a form of stabilization signal as well. Specifically, the authors’ work uses a phase-locked loop (PLL) to actually stabilize drifts in the channels. Sadly, no such thing is bound to be completely perfect and PLL’s do have the chance of not being able to correct the errors quickly enough due to the photons sent traveling at the speed of light. If multiple phase drifts were to occur, without the proper stabilization, the two signals may get mixed up without ever being able to be fixed. Two different types of stabilization are required to prevent errors: one consisting of an independent stabilization and transmission channel, and the second which uses a stabilization loop that uses the errors on the states as a reference signal through the use of an actuator.

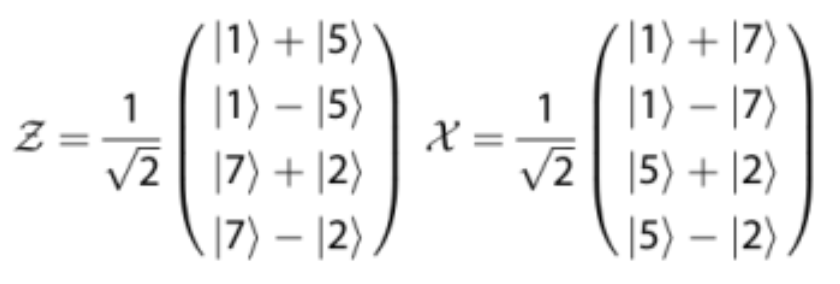

Now to allow for the random state choice, the stabilization channel is integrated with a fast optical phase modulation of the states which requires two mutually unbiased bases shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1. From “Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber”, Da Lio, Beatrice, et al. 2021 These are the two bases used for their work.

There are 8 total states which live on a superposition of just two of the cores, as well as having a pi phase difference to make work easier with the help of a phase modulator (PM). There are going to be a handful of names, do bear with me. Signals need to travel the same optical path as the stabilization channel and must be transmitted in the same fiber to allow for the phase drifts to be properly stabilized. However, as the stabilization signal is phase modulated, there are

interference fringes that happen due to the phase-locked loop (PLL) that cannot be seen, this is the issue involving interference fringes that occur when a stabilization signal is phase modulated. Thus, there needed to be a way to ensure that the interference fringes can then become visualized. The solution involves exploiting the “polarization dependence of PM crystals,” by aligning the polarization of the stabilization signal to be orthogonal to the phase modulator’s modulation axis. This allows for the interference fringes to be seen, and the use of a phase modulation loop (PML), shown in Figure 2 below, is then employed to achieve the desired output.

Figure 2. From “Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber”, Da Lio, Beatrice, et al. 2021. This is the setup of the phase modulation loop which the work uses. The PML consists of a quantum channel (indicated by the red arrow), a stabilization channel (indicated by the blue arrow), a single-mode fiber (indicated by the yellow fiber), a polarization-maintaining fiber (indicated by the blue fiber), a polarizing beam splitter (PBS), a phase modulator (PM), and a polarization controller (PC).

The PML uses the components as depicted in Figure 2 to modulate the phase of the stabilization signal in order to make the interference fringes visible and improve the output. At the end of this process, both of the signals traveling in their respective loops, they will be directed to the PBS’s second input, and it now falls onto Alice to take on the rest.

As we already mentioned, the bulk of the transmission of the information is carried out by Alice, the sender, and Bob, the receiver. However, Alice is tasked with preparing the quantum states and transmitting them simultaneously with the stabilization signal to Bob, via the MCF. This must be done carefully to ensure that the signals are sent out at the same time and that there are no phase drifts. Bob then measures both of the transmitted states and uses them to stabilize the channel. This process is crucial for ensuring the security and dependability of the communication.

Figure 3. From “Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber”, Da Lio, Beatrice, et al. 2021. The entire setup for the work done, it is made up of a quantum channel (indicated by the red arrow), a stabilization channel (indicated by the blue arrow), an intensity modulator (IM), beam splitters (BS), an optical switch (SWITCH), a variable optical attenuator (VOA), a phase modulation loop (PML), a multicore fiber (MCF), a phase shifter (PS), a phase-locked loop board (PLL), wavelength division multiplexing filters (F), and various detectors, including superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (D1, D2, D3, and D4) and InGaAs single-photon detectors (D5 and D6). This is what is used in the transmission of the quantum states between Alice and Bob to stabilize the channel to ensure both the security and reliability of the communication.

The PMLs mentioned above are positioned following the beam splitters to complete the stabilization of signals just prior to being transmitted through the 2km MCF. On the opposite side, or Bob’s side, PLLs are subsequently utilized to stabilize the signals received by Bob. This setup involves the use of two continuous-wave lasers, one for each the quantum and stabilization channel. The light from the first laser is attenuated and turned into a train of pulses, and then these are used by Alice to prepare the quantum states. The stabilization signal is also attenuated and sent through the MCF. Once they reach Bob, the quantum states are measured using superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors, where the stabilization signal is utilized to compensate for possible phase drifts. The entirety of this setup is controlled by a field-programmable gate array board, and the counts from the detectors themselves are then collected by a time tagger. After going through the alphabet soup of components, it all falls upon Bob to just measure both states and continue stabilizing the channel, honestly not too much to ask.

Quantum Protocol

Now, let’s step away from the technicalities of the experimental setup and look at what the authors were able to do with the setup and information from above. After running multiple tests over various periods of time, the team deduced that the best outcomes of transmission were those carried out over a 1-hour period. While 1 hour is nowhere near the rapid speeds that would be necessary for the future commercial and personal use of QKD, nevertheless, this outcome is immensely important for pathing the way for future work to be built upon their findings.

Shown in Figure 4 below is the QBER over time, where the QBER is the ratio between the wrong detections and total detections.

Figure 4. From“Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber”, Da Lio, Beatrice, et al. 2021. This is their data produced over a 1-hour time period.

In red are the results from the X basis configuration, and how the stabilization system instated is able to both track the random phase drifts and compensate for them. This depicts all the stable data, the good stuff we want. The spikes in Figure 4 show times when the PLL lost the locking position. From their data, they were able to determine that using just the switch modulation may result in clear, stable output, however, the output due to the phase modulator does get impacted by phase drifts so this one does end up requiring some form of stabilization to account for those. In the top right corner of Figure 4, there is a zoomed-in portion of the lower part of the graph; from this, we can see that the data points in red are consistently 0.02 higher than the yellow. This indicates what the contribution from the QBER is to be. The average contribution to the QBER from both the stabilization and the phase modulator is 2.8%, thus overall, the study provides good data on the impact of phase drifts on QKD systems.

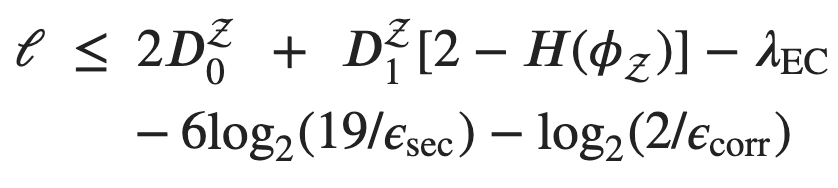

The QKD protocol used here is specifically done through the use of a 4-D path-encoded BB84 scheme by using weak coherent pulses (pulses with the same frequency and phase). The authors use a decoy method to counter the photon number-splitting attack. They find that using

three different intensities for the decoy method is optimal, but using two intensities is more practical. The authors also discuss the impact of phase drifts on the output and the need for stabilization to account for these drifts. Overall, the study provides good data on QKD using weak coherent pulses. For the 4-D QKD protocol, they must use the bound 4-D secret key with one decoy, here they use the following equation to define their ideal secret key length, ℓ as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. From“Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber”, Da Lio, Beatrice, et al. 2021. Depicted is the equation used to define their ideal secret key length.

This secret key length is defined in the paper as being the “number of secret key bits created in a privacy amplification block of length nz.” The following variables are defined: D0Z and D1Z are the lower bounds for the vacuum and the single photon events that occur in the Z basis, H is the function of the high-dimensional entropy where ϕ is the upper bound of the phase error in the Z-basis, λEC is the number of bits that end up being discarded during the error correction process, εsecis the secrecy parameter, and lastly, εcorris the correctness parameter. Now they needed to derive the secret key rate that their setup could achieve, to do so, they had the following fixed values: nZ= 109 bit and εsec = εcorr = 10−15. As well as the two values for the 2 intensities which were found to be the most optimal (μ1 and μ2). Here, Pμ1is the probability of Alice sending a state with the intensity μ1 and PZ is the probability that Alice will choose to prepare in the Z basis OR that Bob will measure in the Z basis. They found the following values for the parameters, which were used for all 4 possible configurations:

1. Z basis and intensity μ1

2. Z basis and intensity μ2

3. X basis and intensity μ1

4. X basis and intensity μ2

After their 1-hour period of running their setup, they obtained the following table in Figure 6. From the data points here, they were able to use their secret key length to determine the secret key rate to be: Rsk ≈ 6.3 Mbit/s. This value was compared to prior work and found that before the secret key rate was ≈ 3.7 Mbit/s, thus showing their work was able to nearly double the prior rate!

Figure 6. From “Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber”, depicting the table of their acquired data.

To get to this value of 6.3 Mbit/s, they, again, used the system shown below and repeated multiple runs for roughly 93 seconds each. This repetition of 93 seconds is the time that was required to create the privacy amplification block, nz. However, in order to replicate their results over much longer transmission distances, they assumed that the signals would experience similar phase drifts. They then used this assumption to emulate the effects of phase drifts at longer distances and added more attenuation to the channel using a variable optical attenuator (VOA).

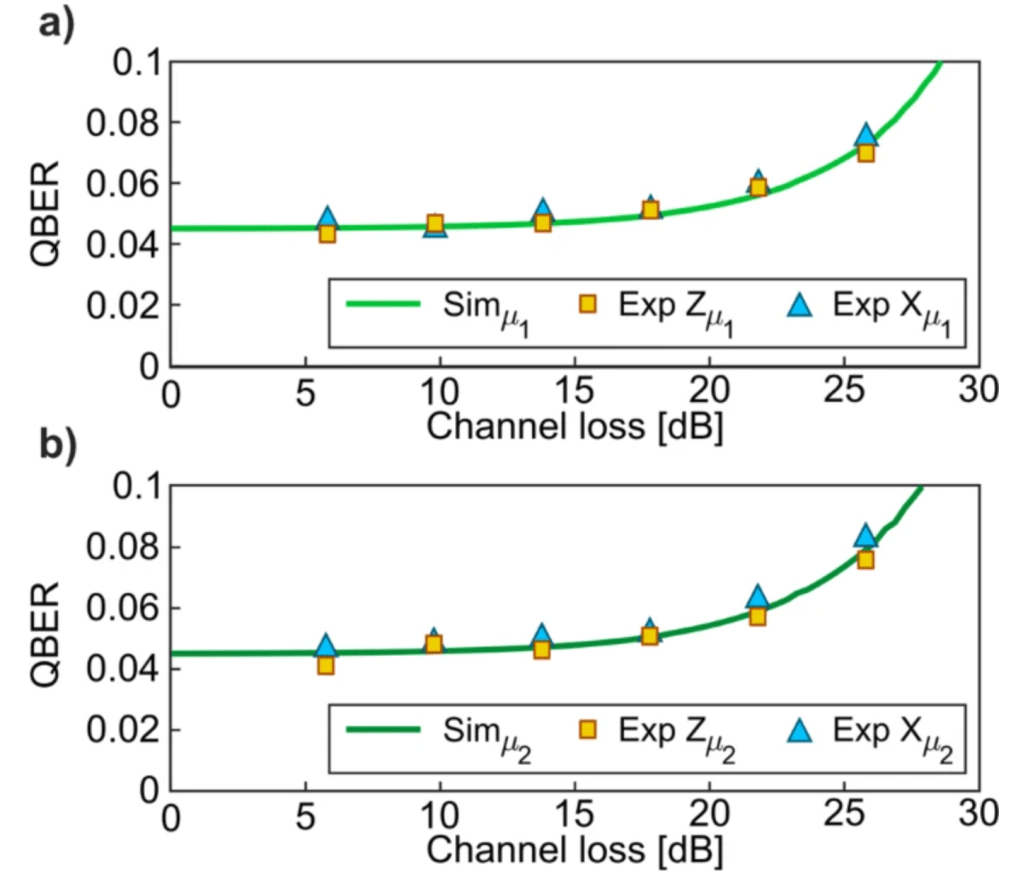

Now the authors took their work and compared it to the simulations to see how their work fit in. Below is Figure 7, depicting the quantum bit error rate, and this graph shows both simulated and experimental data for the Z and X bases for intensities μ1 and μ2. The uncertainty values are computed as the standard error of the mean. The simulation data is represented by solid lines, and the experimental values are represented by yellow squares and blue triangles. Here, the squares and triangles represent the Z and X bases, respectively.

Figure 7. From Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber, depicting the graphs of their channel losses versus QBER.

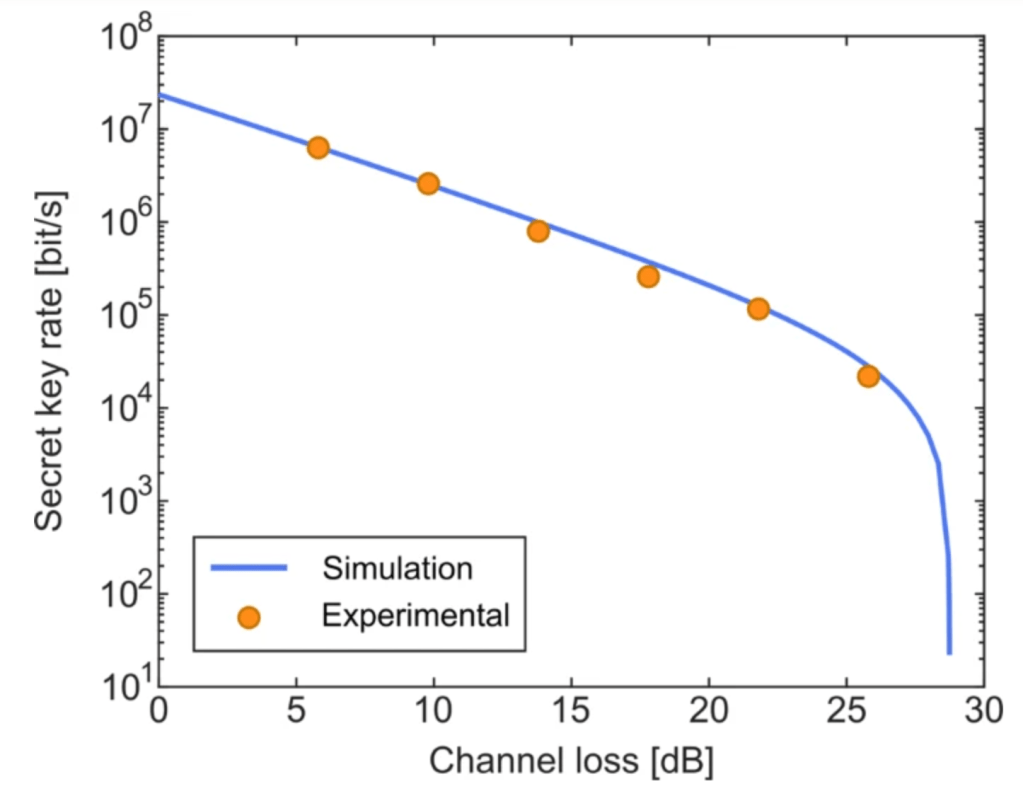

Next, Figure 8 below depicts the channel loss in decibels versus the secret key rate in bits/second. The blue lines depict the simulated values and the orange dots are their experimental values. It is rather clear that these graphs show quite the agreement between the simulated and experimental results!

Figure 8. From Path-encoded high-dimensional quantum communication over a 2-km multicore fiber, showing a graph between the simulation and experimental secret key rates and channel loss.

In Summary

The work which the authors conducted has been able to demonstrate the efficacy of the usage of multicore fibers in combination with a ququart-based system for quantum key distribution. Their work is carried out through the use of a phase-locked loop system to aid in reducing the number of errors caused by phase drifts. To go in hand with phase-locked loop systems, stabilization was required in the form of making use of the polarization dependence that most of the equipment used to encode the quantum states acquired, as well as employing a decoy method and real-time basis choice as other vital components. A comparison of their results to prior work on qubit systems finds that their ququart system has a higher secret key rate. The National Security Agency explains that future uses for high-speed QKD protocol will have major developments in areas such as cybersecurity, but the path to reach this point is a very long one. However, it is evident that further work needs to be carried out on farther transmission distances to make this system commercially viable.

References

Da Lio, Beatrice, et al. “Path-Encoded High-Dimensional Quantum Communication over a 2-Km Multicore Fiber.” Npj Quantum Information, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00398-y.

“Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) and Quantum Cryptography (QC).” National Security Agency/Central Security Service > Cybersecurity > Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) and Quantum Cryptography QC, https://www.nsa.gov/Cybersecurity/Quantum-Key-Distribution-QKD-and-Quantum-Cryp tography-QC/.