Title: Hong-Ou-Mandel Interference between Two Hyper-Entangled Photons Enables Observation of Symmetric and Anti-Symmetric Particle Exchange Phases

Authors: Zhi-Feng Liu, Chao Chen, Jia-Min Xu, Zi-Mo Cheng, et al.

Manuscript: Published 23 December 2022 on Physical Review Letters, [1]

Note: this is part of a series of articles written as final projects for Physics 438b at USC

What is the Hong-Ou-Mandel Effect?

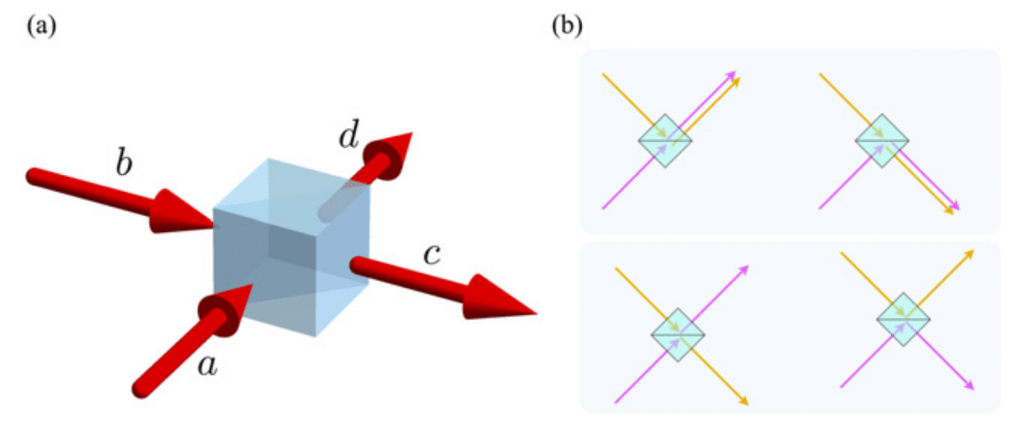

Two-photon interference, termed the Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) effect, has been hailed for being fundamentally quantum with no classical counterpart since its first observation roughly 30 years ago. It is usually implemented with an optical device essential to optical quantum information processing systems, a Beam Splitter (BS), a cube-like instrument as shown below in Fig.1.(a). A beam incident on the BS will be split between two output ports with certain transmittance and reflectance parameters; here we consider the 50:50 BS, where transmittance and reflectance are balanced, thus the incident particle is equally possible to arrive at either of the output ports (for 50:50 BS and different output possibilities, see the right panel of Fig.1).

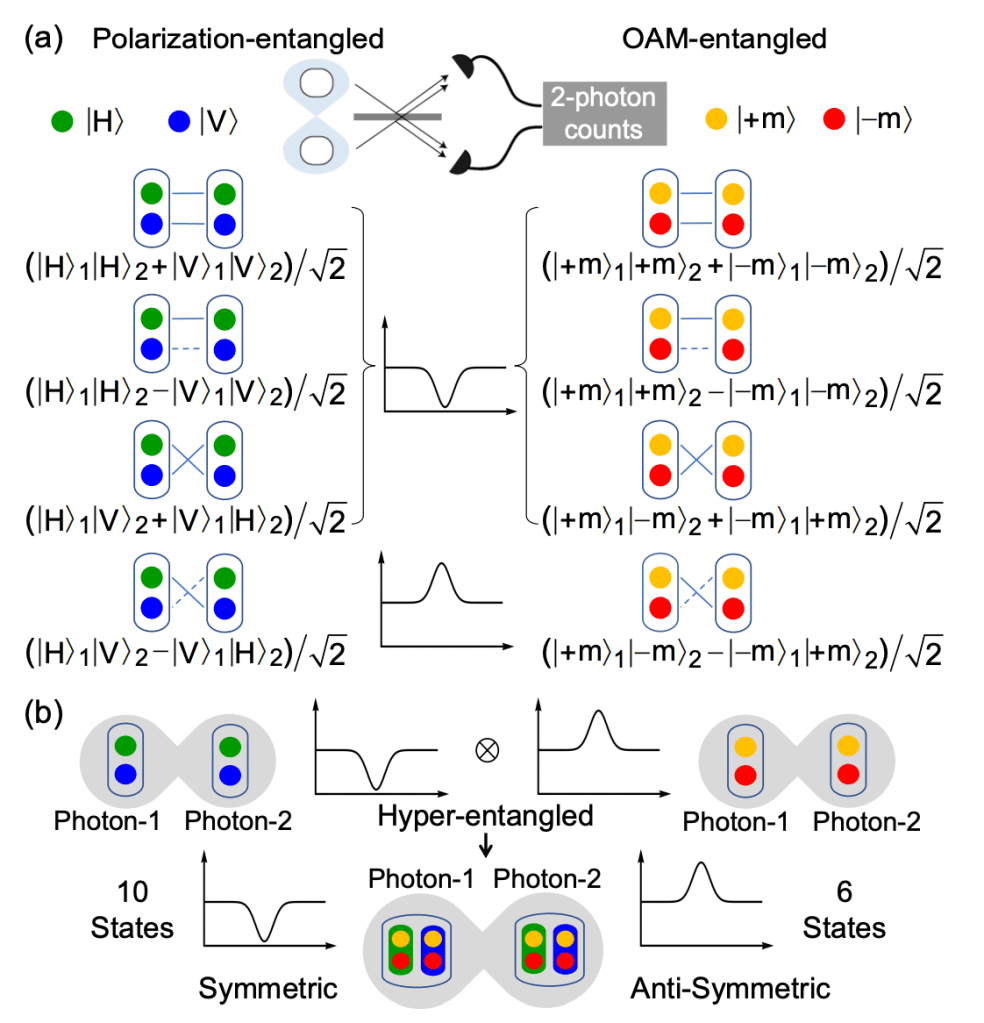

The HOM effect occurs when two indistinguishable photons (those with the same parameters such as wavelength and polarization) are incident at the two input ports, one at each, as the two photons will always come out at the same port. Such interference manifests itself as a dip centered at 0.0 delay on the output graph plotting numbers of coincidences to the delay in emitting the two particles: when they arrive at the same time, they interfere with each other and thus change the output possibilities. A dip is the “bunching” effect as zero coincidence events could be observed when the input particles are bosons that can occupy the same quantum state at the same time according to the Pauli exclusion principle; if they are fermions that cannot, there is observed a peak or an “anti-bunching” result (see Fig.2 and (a) and (b) of Fig.3).

The key to the “quantumness” of the HOM effect comes in at both particle-wave duality and indistinguishability of the photons, which are bosons; two identical photons always arrive at the same output port, since their indistinguishability requires them to be identical in all potential measurements.

Quantum entanglement therefore is inherently linked to the HOM effect, both critical to quantum information processing procedures. Entanglement of two particles can be conveniently prepared with the Bell states: four maximally entangled states that constitute an orthonormal basis to the two-dimensional Hilbert space. If not identical, two photons can differ in a number of different degrees of freedom (DoFs): horizontal or vertical polarization, timing, frequency, or spatial modes. Take polarization as an example, the Bell states are:

Where H and V represent the horizontal and vertical polarization states, and subscripts denote particles 1 and 2. Out of the four, only one has exchange anti-symmetry where swapping the subscripts 1 and 2 lead to an extra minus sign on the overall state:

This state is the Fermion state, where though photons are bosons, their difference in polarization allows states with fermionic qualities as above. The Fermion state exhibits the anti-bunching effect, and the other three states are Boson states that exhibit the bunching effect; picture (a) of Fig.2 illustrates this relationship.

Motivation and the New Idea

One of the key challenges to testing HOM interference experimentally in settings more generalized than identical photons is how to prepare the symmetry or anti-symmetry that the effect relies on. As illustrated above, using the Bell states as input is a convenient solution. Prior to Liu et al. (2022), all the current state-of-the-art experimental research has been limited to using the Bell-state entanglement in only one DoF. But applying the HOM interference in higher dimensions or more DoFs has been an active area of new research: though we will not go into details about them, recently there have been interesting reports on engineering generalized HOM interference with spatial modes (see Hiekkamäki and Fickler (2021) [6]) and structured light along with semi-conductor chips (see Francesconi et al. (2020) [5]).

Liu et al. (2022) presented a way to experimentally explore the HOM interference in two DoFs, adding a DoF of orbital angular momentum (OAM) to the polarization degree, as shown in the right column of (a) in Fig.2. Bell-states hyper-entangled (maximally entangled) photons are utilized in their experiment in order to manipulate the symmetry of the two-photon states.

Moreover, by extending the Hilbert space with one more DoF in OAM, Liu et al. were able to devise a way to control the OAM DoF exchange with the entangled polarization states. In this way they successfully related the external exchange phase in OAM, an initially unmeasurable quantity, into measurable internal phases, thus able to measure the external exchange phase. The concept and implementation scheme of their measurements is explained in the following section.

Setting Up Two-Photon Interference with Two Degrees of Freedom

First, express the initial states of our two photons with a degree of freedom in the OAM, similar to what we did with polarization in the first section. Orbital angular momentum of a particle along a given axis is the magnetic quantum number ; here we take the value of

as a label and let each photon have OAM of

. Their Bell states are thus written as:

Where and

correspond to

, and

is the Fermion state (also shown as the 4th state in (a) of Fig.2).

Now to conduct the generalized HOM effect experiment in two DoFs, we write the states of the two hyper-entangled photons as tensor products of the respective Bell states for each DoF, a way to express the combination of two independent states denoted by ⊗. Since there are four Bell states for each DoF in the two entangled photons, in combination we have sixteen different hyper-entangled states. Depending on whether the states are bosonic or fermionic in each DoF, those 16 states can be divided into four groups. The number, names, and tensor products of these states are shown below:

(1) Fermion-Fermion state:

(3) Fermion-Boson state:

(3) Boson-Fermion state:

(9) Boson-Fermion state:

If a state is a product of two Fermion or two Boson states, we classify it as an even state; if a state is a product of one Fermion state and one Boson state, we classify it as an odd state. This categorization of even or odd, sometimes called “parity of states,” determines the exchange symmetry or antisymmetry, and thus determines the observed HOM effects. Theoretically, it predicts that even states should give the bunching effect like two identical bosons, and odd states should give the anti-bunching effect.

Fig.3 illustrates the results Liu et al. obtained from their two-photon interference experiment in two DoFs, in curves of photon counts to delay. They define a quantity, a way of measuring how pronounced the peak or dip is, called the “extracted visibility of an interference” as:

Where C0 is the fitted count of photons at 0.0 delay, and C∞ is the fitted count at infinite delay. From their observed data, the extracted visibility of the peaks and dips ranges from 0.902 ± 0.071 to 0.993 ± 0.002, all relatively pronounced. As could also be seen straight from the graph, six peaks resulted from the three Fermion-Boson and three Boson-Fermion states, and ten dips resulted from the one Fermion-Fermion and nine Boson-Boson states, just as the exchange symmetry theory would have predicted!

Measuring the Exchange Phase

Liu et al. also proposed that their enactment of the two-DoF two-photon interference can be applied to directly measure the particle exchange phase of the two photons, by introducing a supplementary DoF and creating a superposition between states. To better understand how their measurement works, we’ll first consider the exchange process of a normal two-photon OAM entangled state. The exchange can be written as a unitary evolution process, a process that doesn’t change the magnitude of the state:

Where we say ΦO is the “exchange phase,” and refers to all of the possible OAM states. Note that the OAM state here doesn’t have to be a Bell state, but only one of the Bell states will give an exchange phase of π. For a Boson state in OAM, exchanging the two photons does not make a difference on the overall state, thus ΦO should be 0; on the contrary, for a Fermion state the exchanged state acquires a minus sign, so ΦO should equal to π (exchange anti-symmetric phase) only in the

state of two photons.

In order to create superposition between states in the two different DoFs and extract the external exchange phase, now the authors add on another degree of freedom in polarization, and set up a process to utilize this reference DoF in directly measuring the exchange phase. The designed process is illustrated in Fig.4. They first prepare initial hyper-entangled states with one Boson state in the polarization DoF and an OAM state:

Then pass this state through an optical device named a polarization beam splitter (PBS), which passes the first term in the above state with horizontal polarizations through the splitter intact, but reflects the second term or the vertical polarization components into an exchange. After that, for the vertical polarization components, the OAM portion picks up its usual exchange phase written out above, and the polarization portion picks up an exchange phase ΦP that is known and could be experimentally dealt with by being passed through a Babinet Compensator (BC). As its name indicates, the BC compensates for the polarization exchange phase, returning to its initial both-horizontal-polarization state, but keeping the OAM part intact. I’ll represent this whole process in the equation below:

Overall, the initial state will become:

It is evident that the problem of measuring the external, or global, exchange phase of the OAM is now turned into the much easier problem of measuring the internal phase, or ratio between and

. With the aid of entanglement in the prepared polarization Bell state, we don’t need to measure anything related to the OAM state itself anymore.

To acquire the ratio between horizontal and vertical polarization states, Li et al. projected the polarization state of the two photons onto two sets of states. Both sets are combinations of the state photon 1 is projected onto and one of the states photon 2 is projected onto. The specific combinations are shown below:

Photon 1 projected on:

Photon 2 projected on:

Where the basis for photon 1 primarily functions to leave all of the effects from the OAM particle exchange to photon 2. Photon 2, on the other hand, is projected onto the eigenstates of an observable Mθ defined as follows:

Where σx and σy are respectively the x and y Pauli matrices. The angle θ is a quantity that could be determined in the lab by the orientation of one of the devices used, and could thus be varied by altering that orientation. To get to Mθ then from Li et al’s experiment, start from the photon counts on the two bases and calculate them into relative probabilities P±. The expectation value of Mθ can now be calculated as the difference between the probabilities: P+ − P−.

According to theory, when the value of θ equals the global exchange phase angle we aim to measure, the observable Mθ would reach 1, its maximum value. To confirm the theory, Li et al fed the four different Bell states of OAM into their setup, and the computed values of Mθ from these four experiments are plotted against the θ angles in Fig.5. As predicted, the three exchange phases or θ values are very close to 0 for the three Boson states, and the exchange phase for the Fermion state is . Since their behavior confirms theoretical predictions, now we are able to directly measure the exchange phases by varying θ to achieve Mθ = 1.

Summary and Implication

There have been attempts to generalize the Hong-Ou-Mandel effect to higher degrees of freedom for a few decades now, motivated by its inherent connection with entanglement, the heart of cutting-edge research on quantum information. In this paper, researchers have for the first time systematically, successfully generalized the HOM two-photon interference to two degrees of freedom with two hyper-entangled photons. Their work informs potential new directions and developments for quantum information sciences: the usage of hyper-entanglement provides a method of direct measurement of the exchange phases using an extra DoF that could be generalized to different or more DoFs. Again, we won’t go into the details of them, but the authors have suggested their work could be useful in exploring ideas like alignment-free quantum communications (where the sender and receiver of information no longer need to be aligned) (see D’ambrosio et al. (2012) [3]) and complete Bell state measurements (see Ecker et al. (2021) [4]). In addition, with the aid of new techniques in preparing maximum entanglement in higher dimensions, the HOM effect might be also tested using similar methods in higher dimension and applied to information processing in general.

References

[1] Liu, Z.-F., Chen, C., Xu, J.-M., Cheng, Z.-M., Ren, Z.-C., Dong, B.-W., . . . others. (2022). Hong-ou-mandel interference between two hyperentangled photons enables observation of symmetric and antisymmetric particle exchange phases. Physical Review Letters, 129 (26), 263602.

[2] Bouchard, F., Sit, A., Zhang, Y., Fickler, R., Miatto, F. M., Yao, Y., . . . Karimi, E. (2020). Two-photon interference: the hong–ou–mandel effect. Reports on Progress in Physics, 84 (1), 012402.

[3] D’ambrosio, V., Nagali, E., Walborn, S. P., Aolita, L., Slussarenko, S., Marrucci, L., & Sciarrino, F.(2012). Complete experimental toolbox for alignment-free quantum communication. Nature communications, 3 (1), 1–8.

[4] Ecker, S., Sohr, P., Bulla, L., Huber, M., Bohmann, M., & Ursin, R. (2021). Experimental single-copy entanglement distillation. Physical Review Letters, 127 (4), 040506.

[5] Francesconi, S., Baboux, F., Raymond, A., Fabre, N., Boucher, G., Lemaitre, A., . . . Ducci, S. (2020). Engineering two-photon wavefunction and exchange statistics in a semiconductor chip. Optica, 7 (4), 316–322.

[6] Hiekkamäki, M., & Fickler, R. (2021). High-dimensional two-photon interference effects in spatial modes. Physical Review Letters, 126 (12), 123601.