Title: High-fidelity two-qubit gates on fluxoniums using a tunable coupler

Authors: Ilya N. Moskalenko, Ilya A. Simakov, Nikolay N. Abramov, Alexander A. Grigorev, Dmitry O. Moskalev, Anastasiya A. Pishchimova, Nikita S. Smirnov, Evgeniy V. Zikiy, Ilya A. Rodionov & Ilya S. Besedin

Institutions:

- National University of Science and Technology ‘MISIS’, Moscow, Russia; Russian Quantum Center, 143025, Skolkovo, Moscow, Russia

- Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, 141701, Dolgoprudny, Russia

- Dukhov Research Institute of Automatics (VNIIA), Moscow, 127055, Russia

- FMN Laboratory, Bauman Moscow State Technical University, Moscow, 105005, Russia

Manuscript: Published 08 November 2022 on Nature

Note: This is part of a series of articles written as final projects for Physics 438b at USC.

Background and Motivation

Currently, in the realm of quantum computers and quantum devices, there is an ongoing search for better system architectures to improve reliability and mitigate information loss when performing operations on qubits. These efforts are essential for the advancement of quantum computing, as qubits are inherently fragile and susceptible to decoherence and other unwanted effects. Decoherence occurs when a qubit interacts with its environment in such a way that the original state becomes mixed or entangled with the states of its surroundings. If decoherence occurs, we lose valuable information about a system and cannot perform high-precision operations.

Many recent quantum processor designs involve the implementation of two-qubit gate systems, where transmon qubits serve as the fundamental element upon which quantum gates operate. In quantum circuits, these gates serve as the building blocks that perform operations on the qubits. Transmon qubits, created by a small superconducting island (an island being a region of some superconducting material) connected to a reservoir by a Josephson junction, have been extensively researched in the past decade and are a popular choice for quantum computing. They exhibit low levels of decoherence in comparison to other qubit architectures, enabling transmons to maintain a certain quantum state for a longer period, thus allowing for more reliable operation results. Even so, transmon qubits still have some information loss; for example, they can have lower gate fidelities, which are a measure of how accurately the qubit performs as a quantum gate. Although some transmon qubit systems have almost perfect fidelity (two-qubit systems have been shown to have gate fidelities of ~99.5% according to various demonstrations), there are still other concerns. Crosstalk, the phenomenon in which a quantum state of one qubit affects another, leads to computational errors and decreases the reliability of transmon qubits. Transmon qubits are particularly susceptible to a specific type of crosstalk known as static ZZ interaction, which is a specific type of persistent and undesired coupling that can lead to decoherence and qubit frequency/state shifts.

Because of these challenges, alternative two-qubit architectures with fewer situations for decoherence to occur along with higher gate fidelities are being explored. One type of qubit, known as a fluxonium, is gaining traction in quantum processors and is the subject of this article. Specifically, a fluxonium two-qubit gate system where the qubits are paired to a tunable capacitive coupler could be a novel way of developing scalable NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) devices.

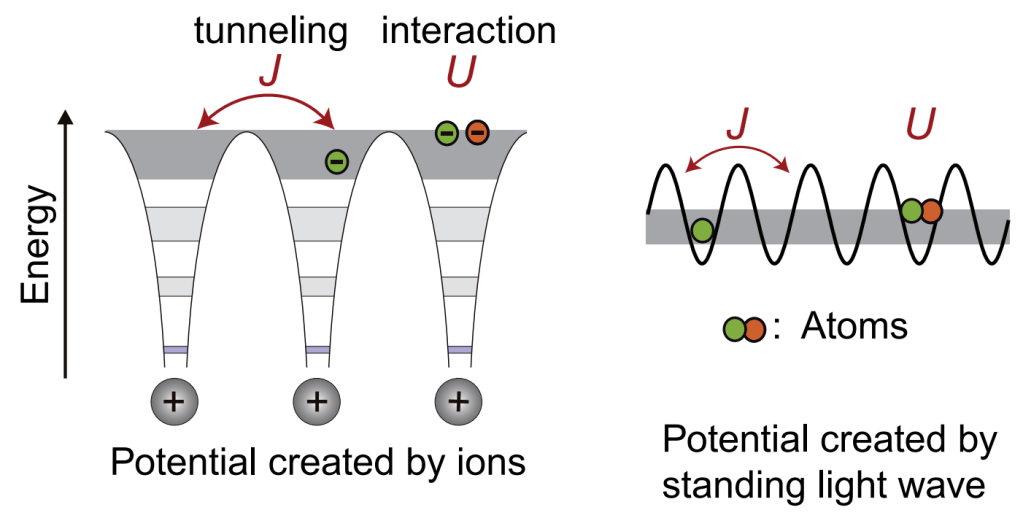

Fluxonium Qubits

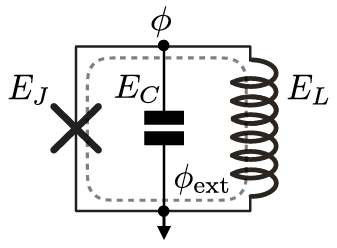

Fluxonium qubits consist of a superconducting loop—different from transmon’s superconducting island—interrupted by a Josephson junction. The Josephson junction has a weak insulating barrier that allows pairs of electrons (called Cooper pairs) to tunnel through it, and through this tunneling, the qubit’s quantum state can be manipulated. When a current is applied to the superconducting loop, it creates a magnetic flux that becomes trapped by the junction. This magnetic flux is quantized, meaning it is discrete in value and can exist only in certain allowed states. These discrete states form the basis of the quantum states of the qubit, and they can be manipulated using quantum gates to perform operations in a quantum computer.

Just like transmon qubits, fluxonium qubits have high gate fidelities and long coherence times, allowing them to maintain a state for a long time without decaying to another state. Fluxonium qubits also have a better level of control over states versus the transmon qubits. Importantly, these qubits are characterized by a lower frequency than transmon qubits. These (resonant) frequencies dictate how the qubit can be manipulated when specific control signals are applied. Fluxonium qubits are also more resistant to information loss and noise, although static ZZ interactions are still a critical issue.

Adding a tunable coupler…

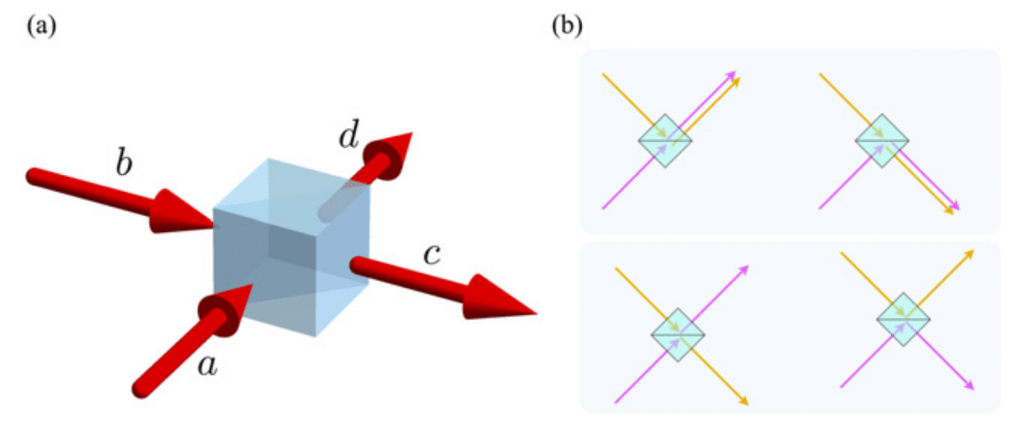

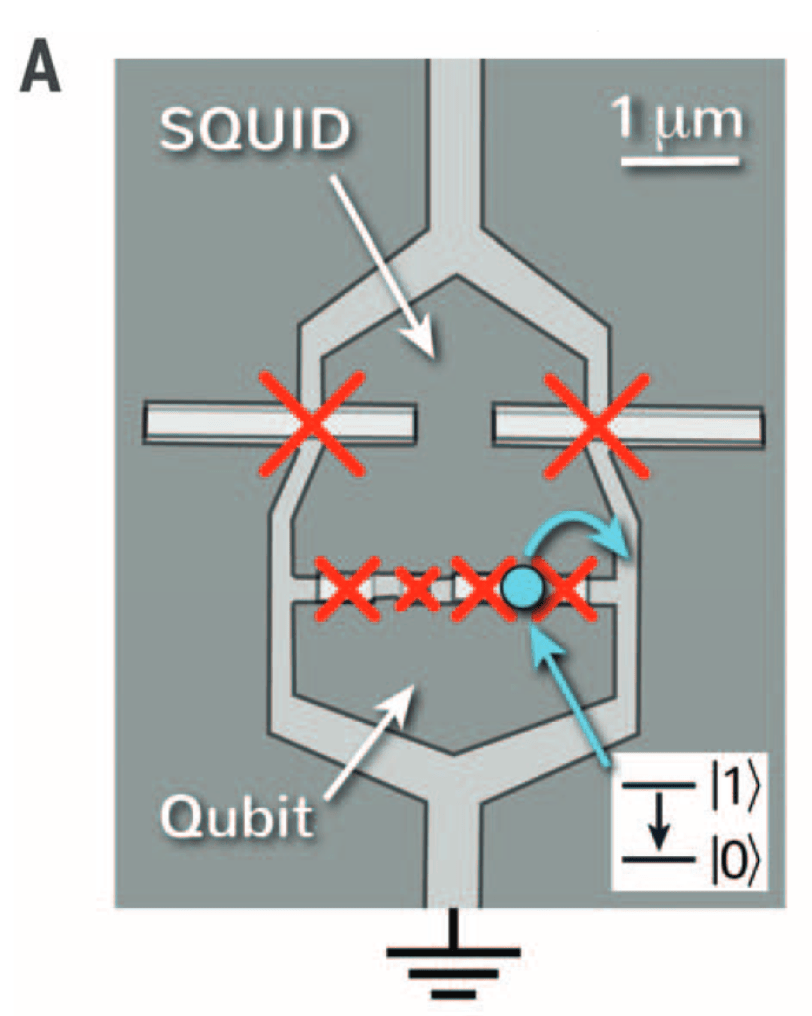

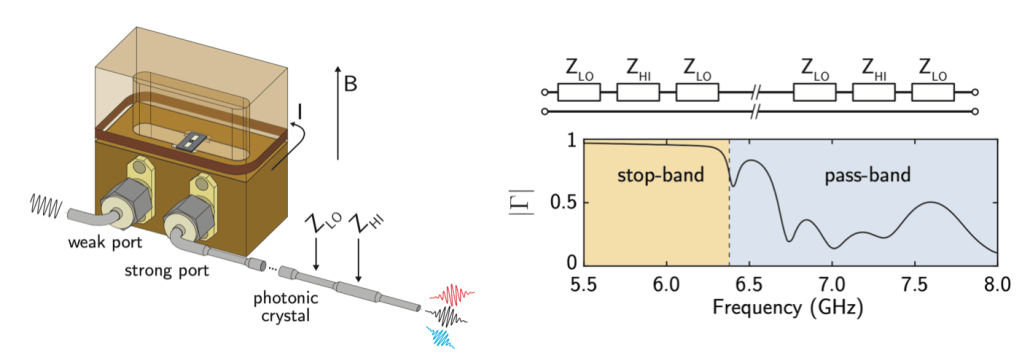

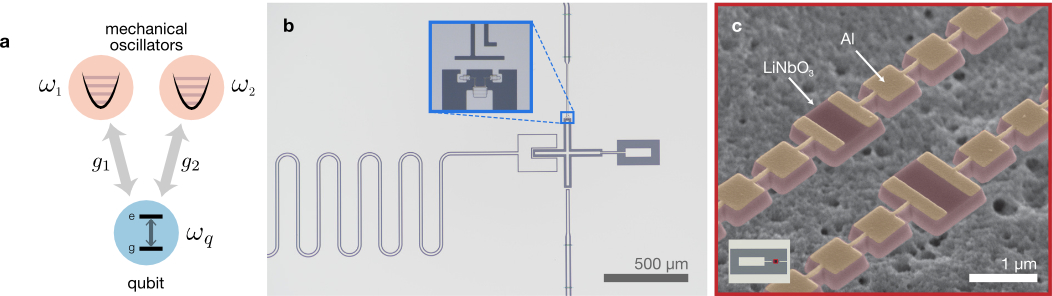

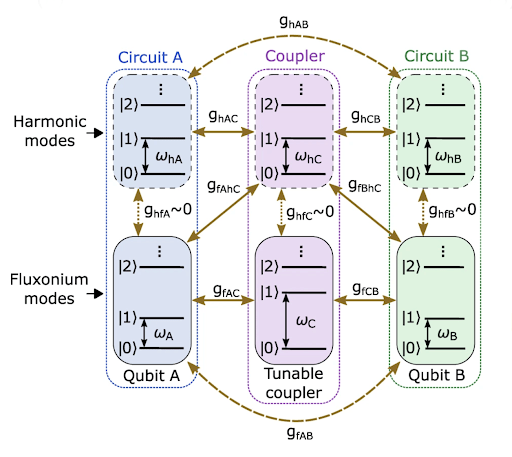

In order to simultaneously increase the gate fidelity and suppress static ZZ interaction in the two-qubit gate processor, the researchers created a processor (see Figure 3) featuring two modified fluxonium circuits (with extra harmonic modes so, therefore, more resonant frequencies) with a central tunable capacitive coupler in which the coupler’s frequencies are controlled by individual fast flux bias lines that are directly electrically connected (galvanically). These are just a type of superconducting circuit that controls the magnetic flux in a qubit. The flux control/bias lines are prone to issues if not developed and implemented carefully; the most relevant issues being attenuation and filtering. Attenuation refers to the loss of signal strength as a control signal transfers through a flux control line which affects the accuracy of the control (since it is difficult to get the sought-after control signal to the qubit). Filtering refers to the removal of unwanted frequencies and noise: if not well designed, it can also remove frequencies from the control signal, which affects reliability. In the case of this article, the individual galvanization allows for independent control of magnetic flux in each bias line. This method of implementing tunable coupling in a quantum computer using capacitive coupling relies on the phenomenon of charge transfer between two objects due to their proximity, to control the interactions between qubits. In this architecture, the qubits are arranged in a specific configuration that allows for this capacitive coupling. By making small adjustments to the distance between the qubits (as well as the size and shape of what they are made of), it is possible to control the strength of the capacitive coupling between them. Just as the qubits have their own frequencies (Qubit A: = 688.224 MHz, and qubit B:

= 664.763 MHz), so does the coupler; in fact, the harmonic frequency of the coupler is

= 2.0 GHz, and this can also be controlled via galvanically coupled fast flux bias lines.2

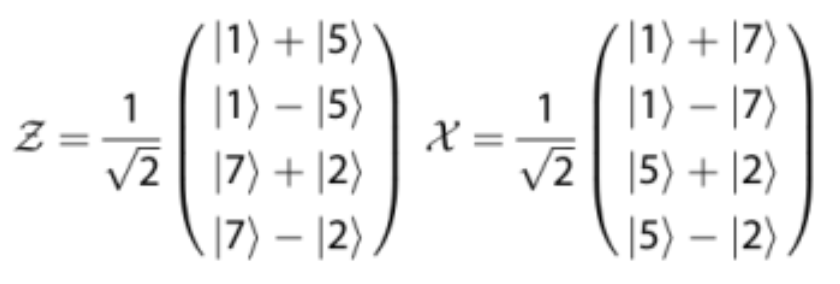

Now, with some careful manipulation to reduce the degrees of freedom of the system, the effective-low energy Hamiltonian of this two-qubit processor becomes:

Notice that this Hamiltonian includes two ‘qubit terms’ and some additional ones as well; the third term relates to the coupling, and the fourth term relates to the ZZ interaction!

Time for Quantum Gates

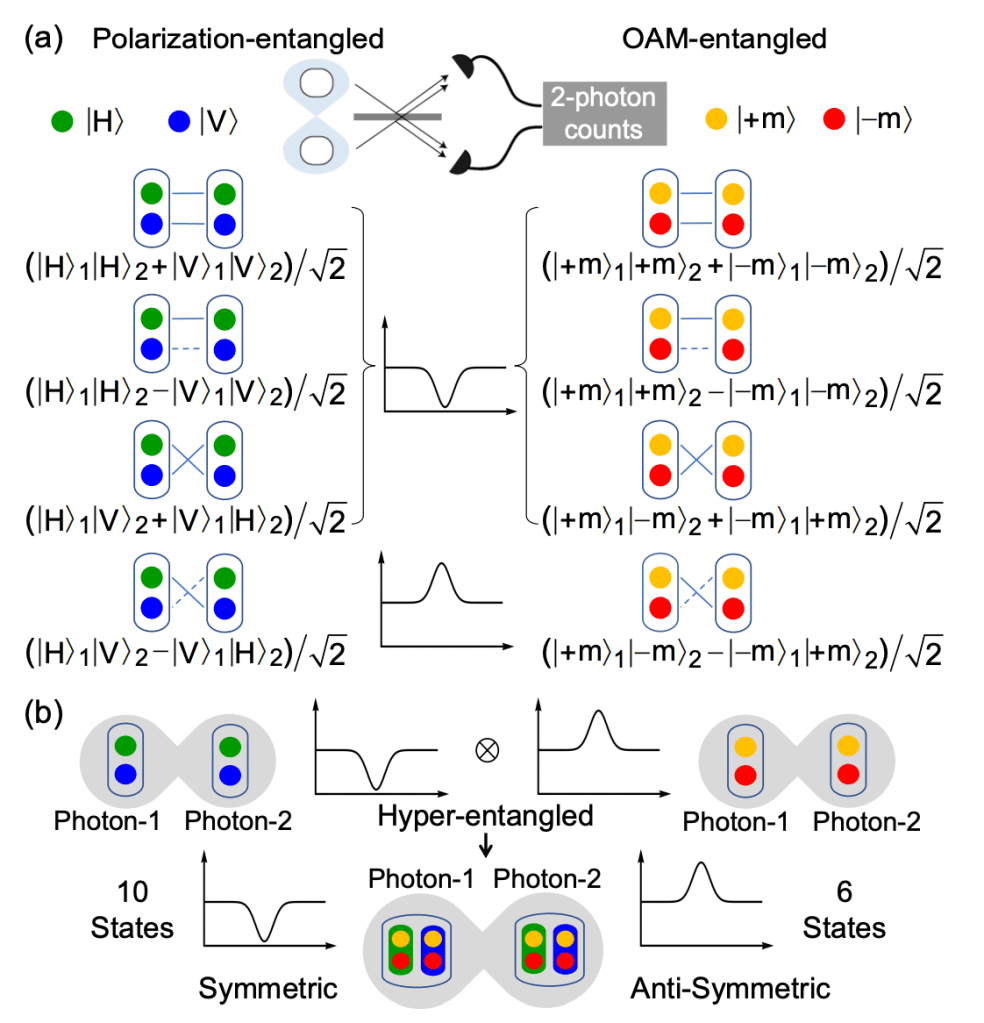

From here, universal gates, which are a set of logical operations that can be used to create any other logical operation, were implemented on the processor using specific pulse sequences. Specifically, the CZ gate and a variation of the iSWAP gate (called the √iSWAP-like gate) were chosen for this purpose; both of these choices derive from what is known as the fSim family. The fSim family is a group of quantum algorithms based on the original fSim (fermionic simulation) algorithm which simulates several different quantum systems, including gates. fSim can be represented with a matrix in the basis which describes a series of rotations that operate on different states:

Where the swap angle determines the strength of the coupling between two qubits, and is a phase shift parameter that is only applied when the two-qubit state is

. This conditional phase shift technique is used to fine-tune qubits’ behavior during specific operations and manipulations.

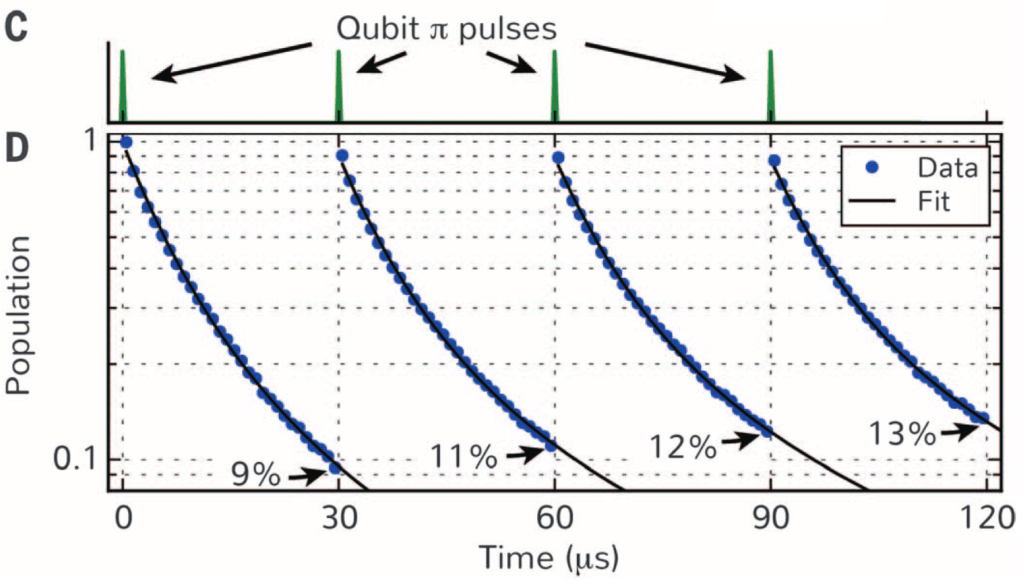

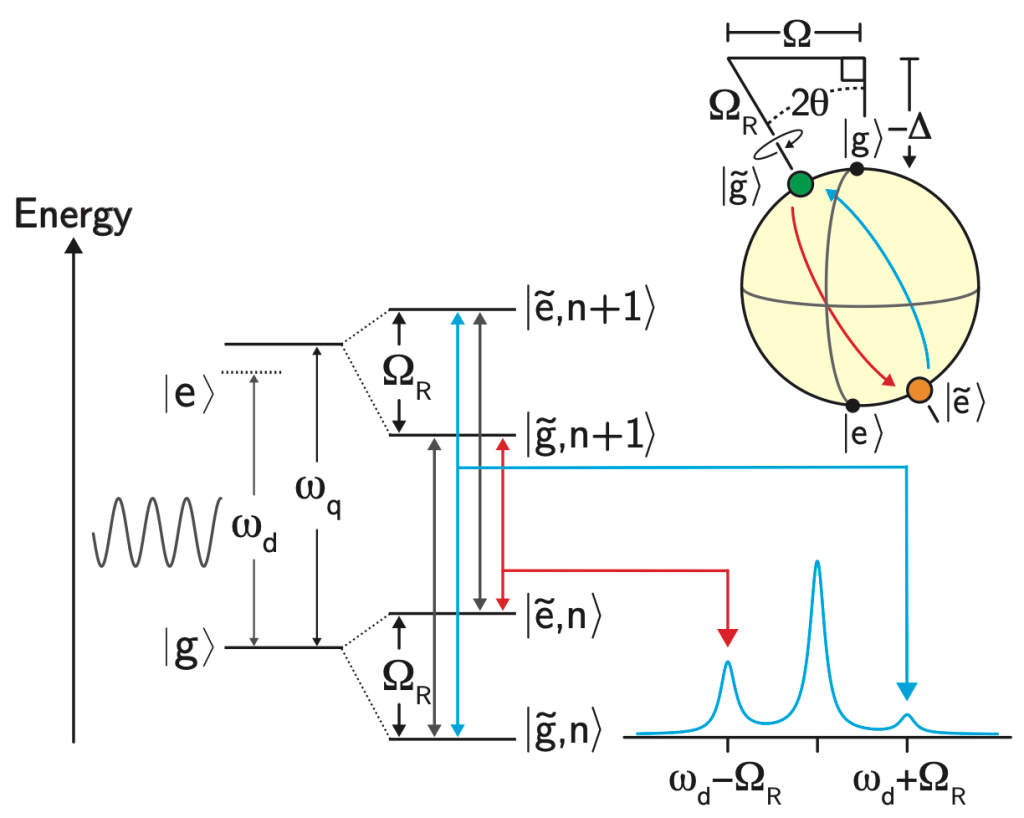

With this in mind, the qubit-qubit coupling term was measured by applying

pulses—controlled electromagnetic pulses of a specific duration and amplitude used to rotate qubit states by 180 degrees—to one of the qubits followed by a modulated flux pulse in order to bring that qubit and the other qubit into resonance. Pulses of magnetic flux are used to control the states of these qubits; these pulses are applied using the galvanized flux control lines mentioned previously, which apply a magnetic field to the qubit in a controlled and accurate way. Calibrating gates this way using sets of flux pulses allowed for the quantification of

against

, which represents various square-shaped flux pulses sent through the coupler bias line.

The researcher’s √iSWAP-like gate (with , or fSim(

) used was implemented using rabi oscillations, which are essentially time-dependent electromagnetic field drives, and were enacted between the

and

states. This √iSWAP-like gate was specifically done by tuning to a specific amount, waiting for a portion of a Rabi cycle, and then detuning back to the original frequency.1 These oscillations modify

in the processor Hamiltonian above.

The CZ (controlled-Z) gate, which was also included in testing because of various precision-related drawbacks the √iSWAP-like gate alone has, was created with two fSim () gates and five single-qubit gates. The CZ gate takes two qubits as input and applies a Z gate to the second single qubit if the first qubit is in the state

. This rotates the state of that qubit around the z-axis of the Bloch sphere. This is reminiscent of entangled states given that the second qubit will only be rotated if the first qubit is in a specific state.

Next, using the coupler flux bias lines, researchers introduced flux pulses that enabled them to precisely modulate the flux. This flux modulation allowed for the qubits to come into resonance. As mentioned previously, these fluxonium qubits operated at a lower frequency than transmon qubits, which allowed the researchers to perform more operations within a period of time without the qubit decaying to a lower state.

Experimental Results

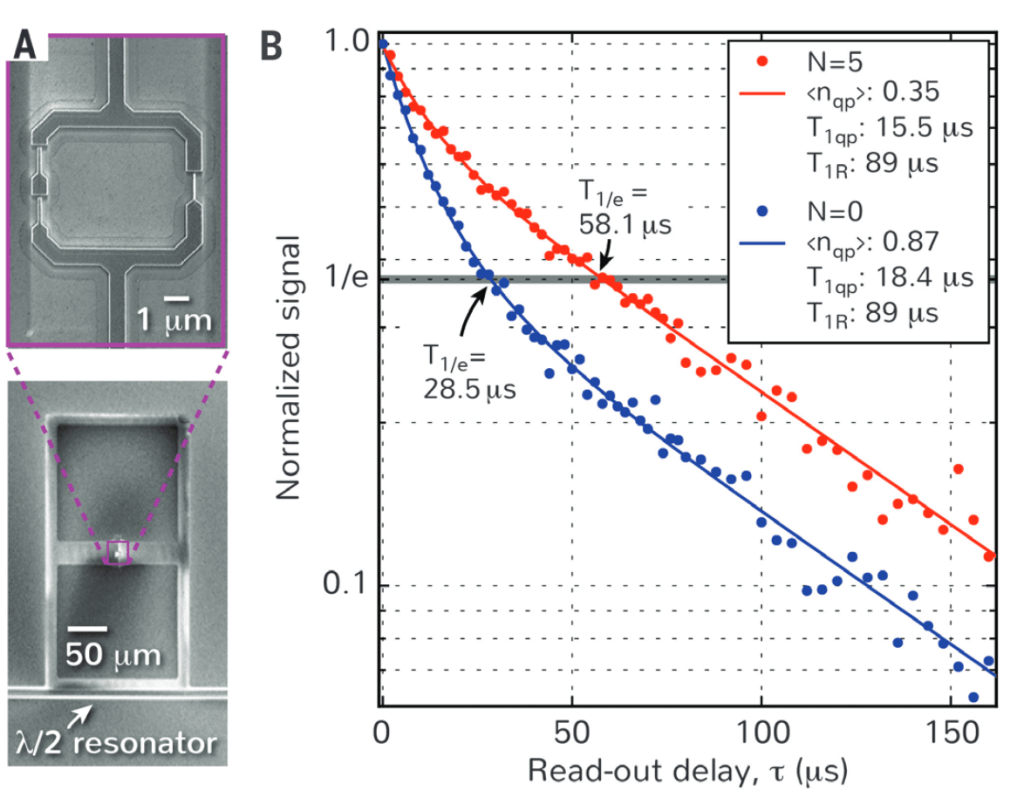

After the implementation of both of these processes, through experiment, it was discovered the static ZZ interaction was almost entirely eliminated (less than 1 kHz remaining!) over a wide range of magnetic fluxes because of the addition of the tunable coupler and the ability to precisely control . This is an extremely valuable result given the ZZ interaction causes decoherence and decreases the reliability of operations on quantum processors.

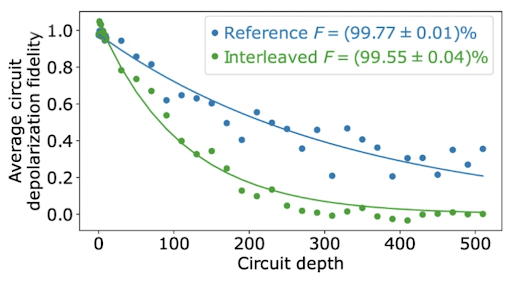

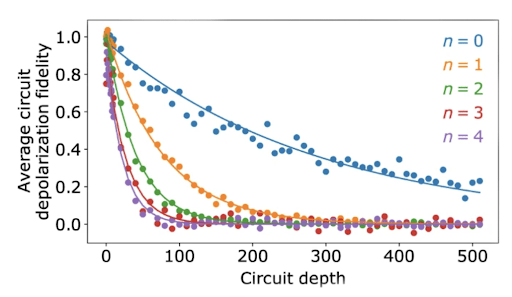

As for gate fidelities of the CZ and √iSWAP-like gates, each was verified using a method called cross-entropy benchmarking (XEB).3 XEB is an algorithm that involves preparing a particular quantum state, performing a specific set of manipulations via various measurement operators, and then analyzing the output of said manipulations probabilistically in comparison to the same state and operations on another (reference) processor/system. In relation to XEB, a parameter called “circuit depth,” which is easiest related to the complexity of a circuit: the greater the depth, the more difficult and resource-consuming the system may be to implement on a quantum computer. Typically it is best practice to minimize this value, although experimentally it was varied to show how the fidelity exponentially decreased as circuit depth increased.

For the √iSWAP-like gate, its resulting gate fidelity was measured to be F = (99.55 ± 0.04)%, as Figure 5 represents with interleaved F. Meanwhile, the CZ gate fidelities were tested using different numbers of CZ gates in a linear sequence; experimentally, the greater the number (n) of CZ gates in sequence, the lower the average circuit depolarization fidelity (see Figure 6). For a single CZ gate alone, the fidelity was measured to be F = (99.22 ± 0.03)%.

Conclusion

In confirming significant static ZZ suppression as well as gate fidelities greater than previously recorded in comparison to processors composed of transmon qubits, it is evident that this processor architecture composed of fluxonium qubits with a tunable capacitive coupler shows that fluxonium qubits are a promising alternative to the popular transmon option in regards to the creation of a quantum processor in which qubits remain in a single state for a longer period of time while maintaining resistance to crosstalk. These two characteristics are essential for the development of future scalable quantum computers. Hopefully, given this success, fluxonium qubits will receive greater attention and experimentation in the near future.

References

1 Moskalenko, I. N., Besedin, I. S., Simakov, I. A. & Ustinov, A. V. Tunable coupling scheme for implementing two-qubit gates on fluxonium qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 194001 (2021).

2 Moskalenko, I.N., Simakov, I.A., Abramov, N.N. et al. High fidelity two-qubit gates on fluxoniums using a tunable coupler. npj Quantum Inf 8, 130 (2022).

3 Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

4 Nguyen, L. B. et al. The high-coherence fluxonium qubit. American Physical Society 9, 4 (2019).